Kendrick Lamar: A voice of a generation

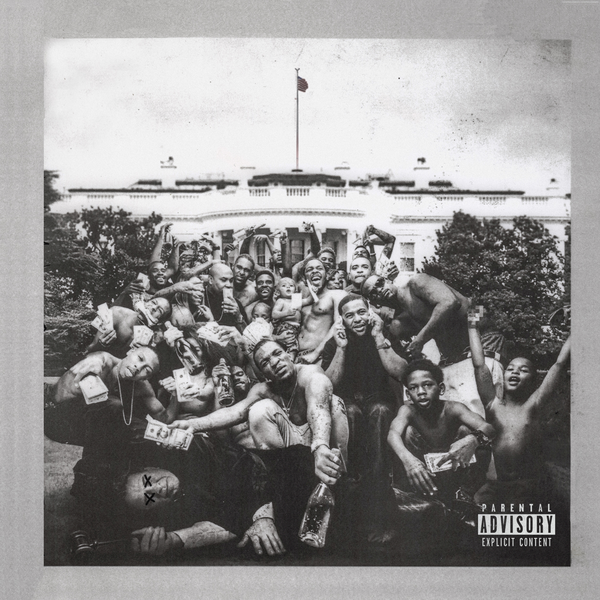

The album art for Lamar’s third album, 2015’s “To Pimp A Butterfly.”

February 27, 2019

Kendrick Lamar Duckworth was born June 17, 1987, in Compton, Cali. Kendrick’s life would change forever at the young age of 8 years old, when he was “inspired” after he saw Tupac Shakur, during the filming of a music video in Compton. Twenty-four years later, that inspiration would come to fruition in ways unimaginable, as Kendrick Duckworth would go on to be held in the same esteem as his childhood idol. One of the most recognizable faces of his generation, widely heralded as one of the most talented and lauded professionals in his field, referred to simply as Kendrick Lamar.

Lamar will undoubtedly retire as the one of greatest rappers in the history of Hip-Hop, but arguably what’s more important, Lamar will go down as one of the most prominent artistic voices of his entire generation.

From his first studio album, it was made quite clear that Lamar wanted to not only dissect the issues that plagued his community, but to try and help combat them as well. The 2011 debut, Section.80, was released by the then-independent record label, Top Dawg Entertainment (TDE). Featuring vocal contributions from fellow TDE labelmates Schoolboy Q and Ab-Soul, as well as Chicago artists GLC & BJ the Chicago Kid, the soundscape of the album feels raw and unpolished, yet there’s clearly a sense of authenticity. Lamar wanted this project to be for the children of 1980s: a reflection of the effects of societal issues on his generation.

Section.80 is a concept album follows the lives of Keisha and Tammy dealing with the themes of racism, substance abuse, the crack epidemic and morality. While it had a mediocre performance from a commercial standpoint, the album received positive reviews and proved to be an auspicious start for one of the genre’s most talented artists. Ultimately, Lamar’s first album was an unfinished sculpture. There was clearly a concept trying to be developed, but the album just lacked some of the refined touches that would create a more audibly cohesive project.

If 2011’s Section.80 was an unfinished sculpture, complete in form, but lacking refined detail, then Lamar’s sophomore LP, good kid, m.A.A.d City, was the finished masterpiece. The 2012 album served as Lamar’s major-label debut (as he signed to Dr. Dre’s Aftermath record label shortly after Section.80) and was a resounding success. The project debuted at number two on the Billboard 200, and the album was greeted with overwhelming praise from critics and fans alike, ultimately picking up four Grammy nominations.

By expanding upon the themes of Section.80 with the usage of a unique, personal narrative structure, the album explored those themes in a far more complex and captivating manner. This narrative structure was the linchpin of the album’s marketing, as the LP was presented as a “short film by Kendrick Lamar.” It is an autobiographical concept album focused on Lamar’s adolescent experiences growing up in the gang-ravaged and drug-filled streets of Compton.

Lamar explained the duality of the title in a interview, saying “It’s two, two meanings. The first is ‘my angry adolescence divided,’ and the basic standout meaning is ‘my angel’s on angel dust.’ That’s the reason why I don’t smoke,” he said. “That was me. I got laced. The reason I don’t smoke, and it’s in the album. It’s in the story. It was just me getting my hands on the wrong thing at the wrong time, being oblivious to it.”

Among the host of phenomenal tracks on the album, two of the standouts include The Art of Peer Pressure (an allusion to the Sun Tzu novel, The Art of War) and Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst. The album’s narrative truly begins with The Art of Peer Pressure, as the track is a vivid tale about a young Lamar feeling pressured into committing a robbery, with the repetitive hook emphasizing the influence of his peers, saying “me and the homies.” Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst is a song that best encapsulates the album as a whole: considered by many as the album’s magnum opus, the 11-minute track is split into two tales of survival in Compton. The first is the story of a person who seeks vengeance through violence, while the second tale is one of a woman who sells herself for money. The latter half of the song is narrated by Lamar, and depicts the story of revenge as he joins the main character on his journey to find the person(s) that killed his brother. Throughout the song Lamar interjects on behalf of himself, discussing his own trials and tribulations throughout his life. The song concludes when an old woman stops Lamar and company, and asks them to join her in prayer instead – an indication of Lamar’s belief that religion can be the true savior of all people in these ghettos.

So how does one top an album that received universal acclaim? They obviously follow it up by releasing arguably the greatest album in the history of the genre – no, seriously. Lamar’s junior effort, To Pimp a Butterfly, was unilaterally considered to be one of, if not the greatest album in the history of Hip-Hop. It was the highest rated rap album of 2015, and the album has an astonishing 96/100 on Metacritic.

The 16-track LP is a nuanced and well-articulated musing on a variety of political and personal themes, including institutional discrimination, depression, racial inequality and African-American culture in general. With a soundscape that drew from jazz, funk, spoken-word and soul, the album’s experimental sound helped to separate itself from any other works that had come before it. Contributing to this avant-garde sound were the contributions from some of the most prominent names in music, such as Dr. Dre, Pharrell Williams, Snoop Dogg, James Fauntleroy and Thundercatt – just to name a few.

This album was Lamar’s first to top the billboard charts, and it has extreme significance for both him and for black culture as a whole. The album dropped during a sort of renaissance of black pride following outcry over a slew of deaths of unarmed black people, and Lamar wanted to tackle a variety of topics that affect the African-American community head on. Songs such as Complexion (A Zulu Love) deal with colorism, Institutionalized deals with the corruptive nature of wealth and the opening track, Wesley’s Theory, alludes to Wesley Snipes’ conviction for tax evasion and deals with the lack of financial knowledge of young men in the African-American community.

Two of the most popular songs on the album, “The Blacker the Berry” (an allusion to Lamar’s favorite rapper, Tupac Shakur, who makes a posthumous appearance on the albums final track) and “i,” work together to tell their own story with the story of the album as a whole. The Blacker the Berry features a hook of “I’m the biggest hypocrite of 2015” and deals with racial self-hatred, whereas “i” features a hook of “I love myself,” and is much more of a celebration of self/blackness. The two work together to mirror the double-consciousness of the black experience. TDE co-president, Terrence “Punch” Henderson, added credence to this idea by tweeting an image of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. side by side.

Following 2015’s To Pimp a Butterfly, Lamar released some of the albums B-sides with the release of the 2016 EP, untitled unmastered. However, Lamar wouldn’t release any new material until he returned with a vengeance on the 2017 single, “The Heart Part 4,” in promotion of his upcoming studio album, DAMN.

Lamar boldly made his intentions known on the ethereal, dynamic track, saying “I said it’s like that, drop one classic, came right back/‘Nother classic, right back/ My next album, the whole industry on a ice pack.”

Two weeks after “The Heart Part 4”, Kung-Fu Kenny released his fourth studio album, DAMN.. The next frontier in Lamar’s musical vision, DAMN. featured contributions from the likes of producers such as Alchemist & Mike WiLL Made-It U2, as well as vocal contributions from TDE-Signee Zacari, Rihanna,and U2, creating a more mainstream-friendly sound than his previous efforts. The mainstream gamble paid off, as the result was a triple-platinum album, Lamar’s third album to reach number 1 on the billboard charts. In addition to commercial success, DAMN. garnered a considerable amount of critical acclaim as well. The album earned “Best Rap Album” at the 2017 Grammy Awards, but most notably the album won a Pulitzer Prize (the first non-classical or jazz artist to win the award).

From his independent debut with 2011’s Section.80 to his most recent studio album, DAMN., Lamar’s artistry has been nothing short of stellar. He hs shown immaculate growth as both an emcee and storyteller, all while handling dense and complex subjects. His transformation from the young Compton street rapper known as “K. Dot” into the international superstar, Kendrick Lamar, is a testament to Lamar’s uncompromising dedication to his craft. Yet, despite the evolution of his sound throughout the years, Lamar’s music has remained authentic and substantive. He doesn’t stay quiet on social issues like some of his contemporaries; he chooses to paint his feelings and opinions on a mural for the world to see.

Unapologetically himself, Lamar is a voice of his generation. The effects of his words may not manifest overnight, but Lamar’s effect on his fans can best be summarized by his idol Tupac Shakur, who once said “I’m not saying I’m gonna rule the world or I’m gonna change the world, but I guarantee you that I will spark the brain that will change the world. And that’s our job: It’s to spark somebody else watching us.”